Buckminster Fuller was a thinker who saw patterns where others saw only sky and stone. He became an inventor, architect, and polymath of the Space Age. Fuller famously called our planet “Spaceship Earth,” emphasizing that humanity is a crew on just one ship hurtling through space without an operator’s manual. This poetic metaphor – Earth as a shared vessel that we must learn to pilot together – became a cornerstone of global and environmental thinking. Fuller’s mission was to help everyone see the big picture of our world’s challenges and our ability to solve them.

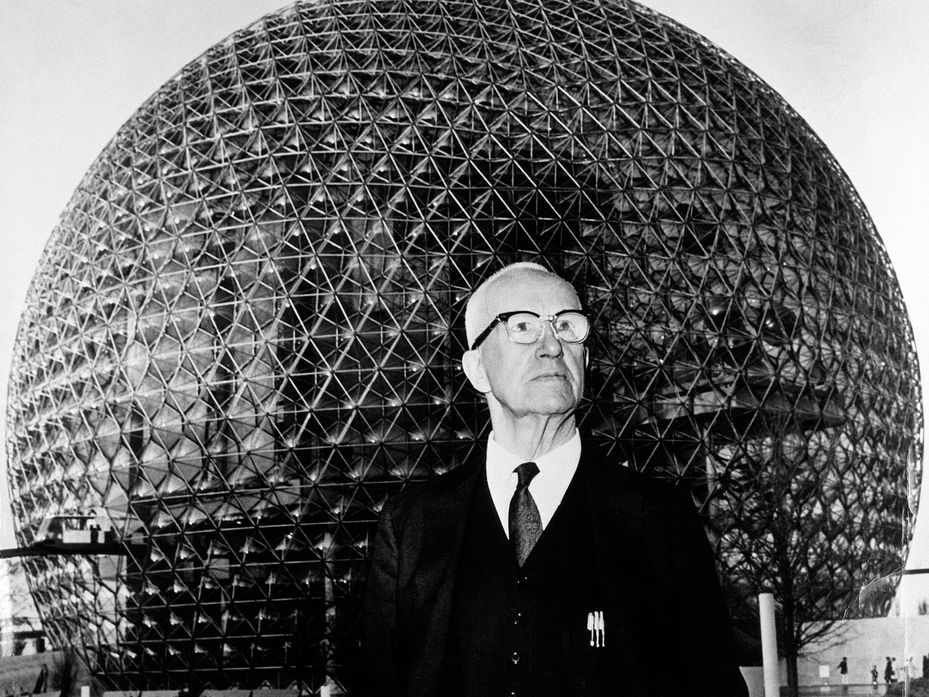

One place where Fuller’s influence is most visible is architecture and design. His geodesic dome is perhaps his best-known creation. Made from a network of triangular panels, these domes can cover enormous interior spaces with minimal materials, making them both strong and efficient. They seem almost to float, their polygonal surfaces shimmering in the sunlight. Dozens still stand today: science museums, university lecture halls, greenhouses, playgrounds, even a few domed homes and churches. Each one is a little Fuller monument. People built tens of thousands of these domes worldwide – a living testament to his vision of doing more with less. Fuller even licensed the dome design royalty-free, so anyone could build one. In this way, his invention literally became part of schoolyards, botanical gardens, and eco-villages across the globe.

Fuller’s impact on mathematics and science was subtler but intriguing. He was not a traditional mathematician, but he loved geometry in an intuitive way. In his book Synergetics, he proposed that complex forms in nature could arise from stacking simple shapes like tetrahedrons and octahedrons. He created the idea of a “vector equilibrium” – a special cuboctahedron where forces balance – which he saw as a fundamental state of balance in the universe. Mathematicians didn’t rewrite their textbooks for him, but many admired his fresh perspective on space and form. In fact, his influence turned up in an unexpected place: in 1985 chemists discovered a new spherical carbon molecule shaped like a geodesic dome, and they named it buckminsterfullerene (nicknamed the “buckyball”) after Fuller. The molecule C60 was exactly like a small soccer-ball of carbon, with hexagons and pentagons just as in his dome design. In this way, Fuller’s geometric vision even predicted an entirely new chemical structure. His love of patterns also led to inventions like the “tensegrity” structure (a mix of tension and compression rods), which found uses from sculpture to engineering, showing that his geometric ideas could cross disciplines.

But Fuller’s legacy runs through design even beyond domes. His Dymaxion inventions were meant to solve everyday problems in revolutionary ways. He created a low-cost, prefabricated “Dymaxion House” as a possible future home – it looked like a shiny pod that could be built quickly to house people affordably. That particular home didn’t become the world standard, but it influenced later notions of sustainable prefab living. Fuller also designed the three-wheeled “Dymaxion Car,” a streamlined vehicle built for speed and fuel efficiency. Only prototypes were made, but the car’s futuristic look influenced later designers. He even drew an unusual flat world map – the “Dymaxion Map” – showing all the continents connected on an unfolded icosahedron. It was his way of pointing out that we often split maps apart, while in reality we live on one connected globe. Though not adopted as a daily map, educators and world citizens use it sometimes to think globally. Fuller wasn’t shy about bold experiments, and his blueprints – whether for housing, cars, or maps – invite people to rethink familiar shapes.

Fuller’s cultural influence was enormous as well. In the 1960s and ’70s, he became a kind of hero for both scientists and countercultural dreamers. He lectured to packed auditoriums about his big ideas, and magazines and TV called him a “traveling salesman for humanity.” The Whole Earth Catalog, an influential magazine of the era, frequently quoted Fuller and even took its name from one of his coined terms (“Dymaxion” stood for “dynamic maximum tension”). Stewart Brand, its editor, later said Fuller’s thinking inspired early computer and tech pioneers. In 2004 Fuller was honored on a U.S. postage stamp as a “great American innovator.” Museums like the Smithsonian and the Museum of Modern Art have exhibited his models and writings, acknowledging that his creative span was immense. He also wrote about thirty books himself, filled with idea after idea. They weren’t always easy reads, but they were like treasure maps – images and diagrams that could spark anyone’s imagination about how to build a better world.

Even beyond the official world, Fuller’s reach is curious. He himself never claimed mystical insights, but he sometimes spoke about love and spirit in almost poetic terms. He even said “Love is metaphysical gravity,” a line that sounds more like New Age wisdom than patent law. Fringe groups – UFO enthusiasts, sacred-geometry devotees, and conspiracy buffs – have absorbed him into their stories. For instance, people fascinated by aliens sometimes see his domes as resembling futuristic spaceships and imagine hidden messages in his maps. Bookshops carry sections of metaphysical books with geometric diagrams similar to Fuller’s, often calling them keys to cosmic consciousness. Notably, Fuller never said anything about extraterrestrials, but the grand vision he set out – the idea of ancient star travelers or divine architects – made his work easy to romanticize. In sacred-geometry circles, his vector shapes are treated almost like holy symbols, and his holistic jargon gets woven into spiritual teachings. It’s an ironic turn: Fuller built a very scientific reputation, but some folks treat his work as if it were mystical or alien-inspired. Nonetheless, even he might have smiled at that – after all, he loved seeing how people can connect ideas across different worlds.

Why is Fuller’s influence so far-reaching? One reason is that he refused to stay in one box. He gave talks and wrote in plain language – often with humor and flair – so artists and activists could understand him as easily as scientists. He patented almost nothing, preferring to give his designs away freely so anyone could use them. This meant people everywhere could build a dome or draw a map his way without worrying about royalties. He spent decades traveling the world, lecturing on six continents and gathering devoted followers. He spoke with United Nations delegates, NASA engineers, schoolteachers, and students alike. Through this, his network of influence multiplied. Another reason was timing: after the atom bomb and into the space age, the world was hungry for new visions. People were ready for someone to show that technology and design could bring peace and abundance. Fuller offered exactly that: he championed using technology to end poverty and even thought wars could become “obsolete” if we just solved resource problems intelligently.

To put it simply, Fuller talked in images and riddles that anyone could grasp. His geodesic dome was a real building, but it also became a metaphor for unity – connecting many parts into one whole. His phrase “Spaceship Earth” sounded technical, yet it resonated like a poem about global togetherness. Engineers saw efficiency; artists saw beauty; environmentalists saw hope. Decades of inventions and lectures gave him a kind of prophetic aura. Even after his death, communities that build domes or call themselves “world-shapers” invoke his name and advice. He once said, “We are called to be architects of the future,” and indeed he designed parts of that future literally and figuratively. His words and structures have become part of the scaffolding of our modern world: from the dome of a stadium to the concept of a “global mind.”

Buckminster Fuller once urged us to make the world work for 100% of humanity – a vision that still inspires people today. Decades later, the blueprint of his optimism is woven into the geometry of our buildings and the language of our ideas. He planted memes like “Spaceship Earth” and “doing more with less” into our culture. Even if only a fraction of people know his name, his fingerprints are on many things we now take for granted: from the roofs over our heads to the slogans of sustainability. In that sense, the world he imagined is still being built all around us. His influence has shaped the roof over our heads and the dreams of our future, and his vision remains a guiding star for those who want to design a better world.