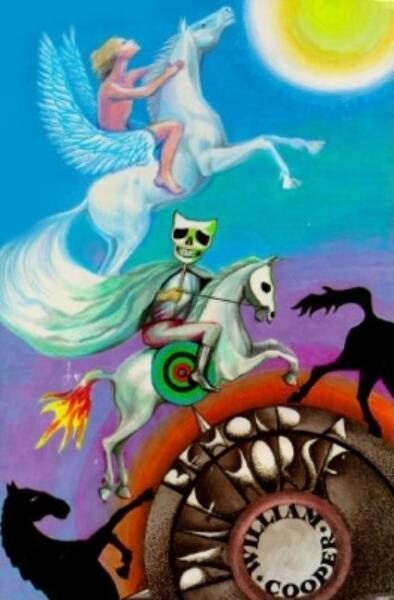

On a November night in 2001, in the high desert of Arizona, a peculiar chapter of American conspiracy lore came to a violent end. Milton William “Bill” Cooper—an ex-Navy radio broadcaster turned author—died in a shootout with sheriff’s deputies on his own property, guns blazing. Cooper had often declared he would never be taken alive, so in a grim way, his end was a final broadcast of his beliefs. This dramatic climax was befitting of Cooper’s life work, for he had spent years warning anyone who’d listen that shadowy forces were out to enslave the common citizen. His seminal book, Behold a Pale Horse, first published in 1991, had become a cult artifact by the turn of the millennium—a dog-eared bible of conspiracy theorists across the country and beyond. In its pages, readers found a dizzying grand narrative: secret societies controlling governments, extraterrestrial alliances with the U.S. government, plots to create a new world order, and even reprints of alleged secret documents like the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion. At gun shows, militia gatherings, and late-night dorm room discussions, Behold a Pale Horse passed from hand to hand, its eerie title and contents fueling suspicions about everything from the Kennedy assassination to AIDS. Decades later, even as Bill Cooper’s voice fell silent, the echoes of his paranoid prophecy found new life in the digital age. One need look no further than the rise of QAnon in the late 2010s—a sprawling, baseless conspiracy theory movement—to see the fingerprints of Cooper’s legacy. The roots of today’s false and dangerous conspiracy theories, including QAnon, trace back through a lineage of fringe ideas that Behold a Pale Horse crystallized and popularized. By examining this lineage, we can better understand how such theories spread and, critically, how recognizing their origins might help society break the spell of fear and hate that they cast.

Behold a Pale Horse

Bill Cooper was a man of contradictions: a military veteran who turned vehemently anti-government, a self-styled patriot who came to be labeled an extremist, and an underground icon whose work unexpectedly permeated mainstream culture in curious ways. Born in 1943 and raised in a military family, Cooper served in the Navy during the Vietnam War era. He later claimed insider knowledge from his time in naval intelligence—stories of seeing classified documents that revealed the U.S. government’s secret pacts with alien beings, for example. Whether or not any of those claims held truth (most have been debunked or lack evidence), they formed the seed of Cooper’s emerging worldview. By the late 1980s, he had started broadcasting his ideas via shortwave radio, speaking to an audience of fellow travelers who distrusted the official narratives of the Cold War and beyond. In 1991, he compiled his fears and findings into Behold a Pale Horse. The book’s title, drawn from a passage in the biblical Book of Revelation, hinted at apocalyptic content—and it delivered.

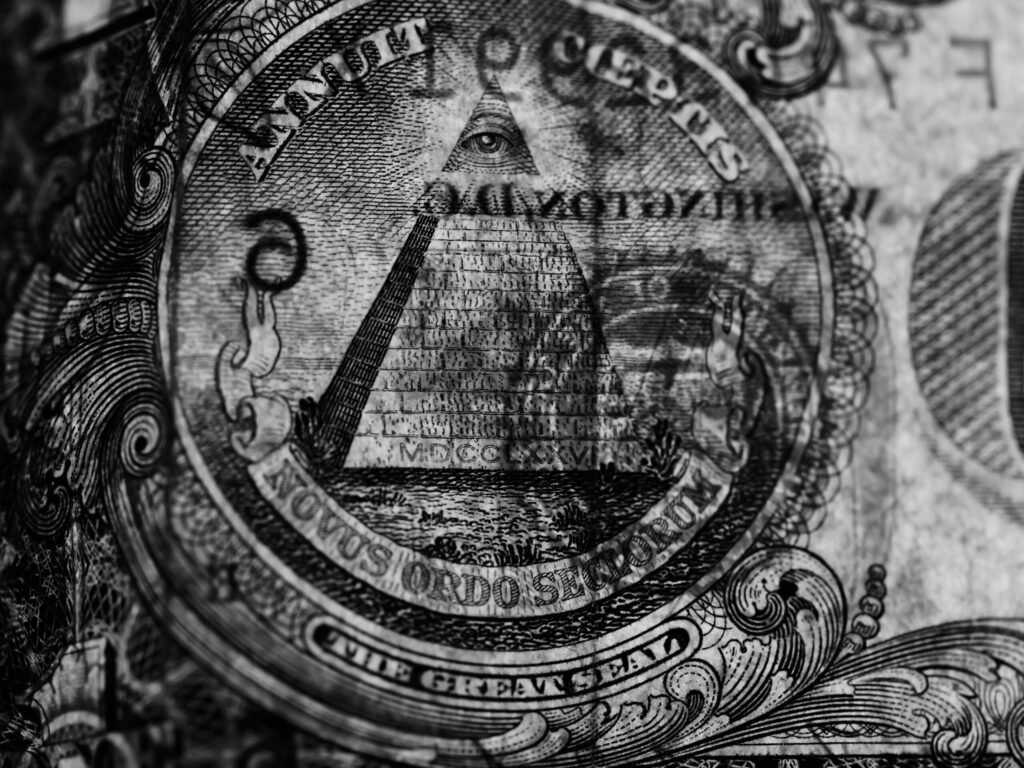

Between the covers of Behold a Pale Horse, readers found a mixtape of virtually every conspiracy theory circulating at the time, blended into an overarching nightmare vision. Cooper asserted, for instance, that the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was orchestrated not by a lone gunman, but as part of a secret elite plot—going so far as to argue an absurd twist that the presidential limousine driver was complicit in the shooting, using alien weapon technology. He warned of an impending “New World Order” in which international bankers and clandestine societies like the Illuminati would abolish American freedoms. UFOs and aliens were not fantasy for Cooper; they were integral to his narrative. He insisted that extraterrestrials had been in contact with Earth’s governments and that events like the notorious Roswell incident were just the tip of a cosmic iceberg. The government, he said, knew the truth and kept it from the people, possibly preparing for an eventual fake alien invasion to justify global authoritarian rule. If this sounds dizzying, it was. The book bounced from topic to topic: one chapter might delve into the evils of a coming one-world government, and the next would reproduce “Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars,” a purported secret document outlining a plan to control populations through technological means. Buried in the compendium was also Chapter 15, a reprint of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a notorious anti-Semitic hoax document from the early 20th century, which claimed to expose a Jewish plot to dominate the world. Cooper presented it as if it were a real leaked plan from the Illuminati (with some names swapped, suggesting readers substitute “Illuminati” for “Jews” in the text). This inclusion was deeply troubling—Protocols had been the basis for countless acts of hatred, including inspiring Nazi ideology—yet in the early 90s, many of Cooper’s readers either didn’t recognize it or took it at face value as further proof of villainous elites. The publishers of the book actually removed the Protocols chapter in later printings due to its toxic nature, but by then the damage was done; the text was out there and being believed by some.

Cooper’s work gained traction in subcultures that felt disenfranchised or skeptical of authority. Within the burgeoning militia movement of the 1990s—groups of armed civilians convinced that the federal government was on the verge of tyranny—Behold a Pale Horse was revered. The British newspaper The Guardian once dubbed it “the manifesto of the militia movement.” Its popularity wasn’t confined to one demographic. Interestingly, the book found an eager audience in some urban communities and prisons. Inmates passed the time poring over its pages, finding in it an explanation for why society felt stacked against them. Even elements of the hip-hop scene picked up on Cooper’s ideas; rappers from the Wu-Tang Clan and others name-dropped or read his work, intrigued by the notion of hidden hands controlling the fate of Black America and the world. In a way, Bill Cooper inadvertently became a bridge between rural militiamen and inner-city youth—a testament to how conspiracy theories can leap across usual social divides, united by a shared distrust of power.

All the while, Cooper continued his radio show The Hour of the Time, railing against whatever he saw as the latest evidence of creeping tyranny. When the tragic bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building happened in 1995, it emerged that Timothy McVeigh, the anti-government terrorist responsible, had been a fan of Cooper’s broadcasts. This cast an even darker shadow on Cooper’s influence. He condemned the bombing, but the fact remained that his rhetoric of government evil had been cited by someone who turned rhetoric into violence. Cooper’s final years were spent increasingly embattled—he was charged with tax evasion and became a fugitive, convinced that federal agents were coming for him (and indeed they eventually did). His death in 2001, just a few months after the September 11 attacks, came at a time when he had been one of the first to suggest that Osama bin Laden would be a convenient scapegoat for a huge incident—he made that prediction in June 2001, remarkably presaging the exact conspiracy theories that would follow 9/11. To his followers, it was proof that he foretold the truth; to others, mere coincidence. Either way, Bill Cooper exited life as dramatically as he had lived it. But the ideas he promulgated did not die with him. In fact, they were only gathering strength, waiting for the right medium and moment to explode into the mainstream.

The Seeds of QAnon

Fast forward nearly two decades after Behold a Pale Horse. The year is 2017 and on an anonymous corner of the internet—specifically the murky message board 4chan—a user claiming to have high-level U.S. security clearance begins posting cryptic messages. The user signs off as “Q.” These “Q drops,” as they came to be called, spun an elaborate yarn: they claimed a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles had infiltrated the highest levels of government, business, and Hollywood; that this evil cabal was secretly controlling world events (from rigging elections to running child trafficking rings); and that President Donald Trump was quietly working with “patriots” in the military to expose and destroy this cabal. A day of reckoning called “The Storm” was coming, Q hinted, when mass arrests would sweep the traitors away. To those versed in conspiracy history, this all sounded eerily familiar. Replace “Satan-worshipping pedophiles” with “Illuminati Jewish bankers” or “alien lizard people” or any past bogeyman, and the pattern emerges: the world is run by a hidden evil; only a small group of enlightened truth-tellers see it; a savior or righteous uprising is needed to reclaim the world for the people. It was the old template of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, of anti-Communist Red Scare hysteria, of New World Order paranoia, repackaged for the age of social media and hyper-polarized U.S. politics.

QAnon, as this movement came to be called, quickly moved from fringe internet forums to larger platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, drawing in tens if not hundreds of thousands of believers worldwide. By 2020, QAnon’s presence was visible offline: followers wore “Q” T-shirts at political rallies, conspiracy-laden hashtags trended online, and tragically, some adherents committed violent acts inspired by the theory (most infamously, the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, where QAnon slogans and symbols were on display among the crowd). The FBI went so far as to label QAnon a potential domestic terror threat due to its potential to incite violence from extreme believers. How did a conspiracy theory so bizarre gain such traction? One answer lies in the groundwork laid by figures like Bill Cooper.

Cooper’s Behold a Pale Horse was essentially a precursor to QAnon in content, if not in form. The narrative QAnon pushed—that a secret cabal manipulates world affairs and preys on children, and that only heroic patriots can stop it—echoes the themes from the Protocols which Cooper had helpfully included in his book decades earlier. In Protocols, the supposed conspirators were Jews; QAnon updated the cast to “globalists” often insinuated to be liberal politicians or financiers (with anti-Semitic undertones still present, as figures like George Soros or the Rothschild family frequently feature in Q lore as villains). The core antisocial fantasy—that someone out there is doing horrible things to children and controlling everything—never died in the paranoid imagination. It just took on new names and faces.

Moreover, Cooper’s style of connecting disparate events into one big theory prefigured how QAnon followers would interpret real-world happenings. Cooper taught a generation of conspiracy enthusiasts to take nothing at face value, to weave even the most unrelated tragedies or political decisions into a single tapestry of plot. We see this in QAnon: A pandemic is not just a pandemic, it’s a plandemic orchestrated by the cabal. A ship stuck in the Suez Canal must secretly be carrying trafficked kids for the elites. A blackout in one city might be a cover for secret arrests. This pattern of thought—everything is evidence of the conspiracy—was nurtured through years of alternative media and underground chatter that Bill Cooper helped popularize. In fact, the medium shift from shortwave radio and photocopied zines of Cooper’s time to the algorithms of YouTube and Facebook groups in QAnon’s time made the conspiracy web even stickier. It allowed these ideas to ensnare people who might never have stumbled upon a militia meeting or UFO convention.

There are direct lines of influence too. By the 2010s, Behold a Pale Horse had sold well over a quarter-million copies and likely reached millions more through pirated PDFs and online forums. On far-right and conspiracy websites, Bill Cooper was often revered as a kind of prophet. Ironically, Cooper himself, were he alive, might not have embraced QAnon—he was notoriously territorial and had denounced other conspiracists like Alex Jones as alarmists or frauds (Cooper took pride in what he saw as his own genuine conviction). A biographer of Cooper once suggested that Cooper would have seen QAnon as competition and therefore disdained it. But even if the personalities might have clashed, the content overlaps significantly. QAnon’s fixation on “children in peril” (the baseless claims of widespread child exploitation rings), its distrust of government (the “deep state”), its fear of globalist agendas—all of these were present either explicitly or in germ in Cooper’s work.

Another crucial aspect is how conspiracy theories often carry implicitly fascist and white supremacist narratives. Cooper’s material, by recycling the Protocols trope, inadvertently carried forward an old European anti-Semitic storyline, although he reframed it as anti-Illuminati. QAnon similarly paints its enemies with traits long used in anti-Jewish libels (child-murder, world domination) and merges them with American far-right talking points (gun control fears, anti-immigrant sentiment by warning of “open borders to mongrelize the race” as QAnon rhetoric sometimes goes). When you peel back QAnon’s layers, you find specters of old fascist propaganda dressed up in American flags and internet memes. The conspiracy narrative requires a scapegoat—a shadowy “Other” responsible for society’s ills. In Nazi Germany that was Jews, in QAnon it might be liberal elites or Hollywood pedophiles or Chinese communists or all of them at once in one great amalgam. The pattern of fear and blame remains, and it follows lines that often target marginalized groups or reinforce a myth of a pure people betrayed by hidden traitors. This is precisely how fascist movements gain footing: by uniting followers against demonized enemies with wild accusations, and by offering the intoxicating promise that a strong leader (be it Hitler or a supposed secret Trump-led military intel team in Q’s telling) will restore greatness by vanquishing these demons.

Understanding this trajectory—from Bill Cooper’s Behold a Pale Horse to QAnon’s digital wildfire—is more than a history lesson. It is a key to disarming the allure these conspiracy theories hold. When we recognize that QAnon is not a novel revelation but rather “a repackaged cult doctrine” with roots in the ugliest lies of the past, we demystify it. It loses the sheen of being a bold, secret truth and is revealed as a recycled fiction. Illuminating the lineage of conspiracy theories can help would-be believers see the puppet strings of history at work. For instance, learning that the tale of a secret cabal of child-eating elites originated in medieval and then Tsarist anti-Jewish propaganda—and led to real-world horrors—might give pause to someone tempted to take QAnon at face value. It invites the question: If I reject the bigoted lies of the past, should I not also question their modern variant?

Moreover, understanding figures like Bill Cooper humanizes the phenomenon of conspiracy belief. Cooper was a living, breathing person with certain experiences that led him to embrace the conspiratorial worldview. He saw real government deceit (Watergate, Vietnam-era lies, etc.) and extrapolated to universal deceit. He had personal disappointments and perhaps a need for importance that his conspiracy crusade fulfilled. Recognizing those human motives can engender empathy for why neighbors, friends, or family today might slide into believing QAnon’s far-fetched claims. It’s often not because they are stupid or inherently hateful; it’s because the narrative is compelling to some emotional need—be it fear, or a desire for clarity in chaos, or a sense of belonging to a grand struggle of good vs evil. By tracing how these theories evolve, we also see how each era’s anxieties get woven in. In Cooper’s time, it was UFOs and Cold War paranoia; in QAnon’s time, it’s partisan political rage and the anonymity of the internet fueling fantasies. This context helps us address the root causes: mistrust, alienation, and the seduction of simple answers.

Crucially, exposing the roots of conspiracy theories can undercut their power to drive society toward dangerous extremes. QAnon and its ilk have shown a frightening capacity to radicalize individuals, pushing some toward violence or at least toward supporting anti-democratic, authoritarian measures under the guise of fighting evil. These conspiracies often carry an implicit call to action: “Do something before it’s too late—stop the steal, save the children, fight the secret war.” It is not hard to see how that call, if acted upon en masse, trends toward fascistic outcomes: militias taking the law into their own hands, or citizens willing to suspend democratic processes to allow a strongman to crush the imagined cabal. The January 6 Capitol riot was one manifestation of this dynamic, with insurrectionists convinced they were heroes of their own narrative. If more people had recognized that they were being manipulated by a reincarnation of age-old lies, perhaps fewer would have been drawn into that mob.

Education and transparency are our society’s best weapons against falling into a truly fascist, white-supremacist abyss under the spell of conspiracies. For every sensational claim, showing the factual history can act as a reality check. For example, when QAnon believers circulated blood-curdling rumors of a global child-trafficking ring centered in a pizzeria (the debunked “Pizzagate” theory that preceded QAnon), debunkers pointed out how this mirrored the medieval blood libel against Jews. Those parallels are not coincidental—they reveal the hateful DNA of the myth. By teaching these connections in schools, media, and public discourse, we cultivate a kind of herd immunity to conspiracy thinking. People might still flirt with such ideas, but armed with historical knowledge, they are less likely to be fully ensnared, and more likely to question the narrative and the motives behind it.

Even within the world of conspiracies, learning about Bill Cooper’s full story can be instructive. Cooper spent his final years effectively consumed by the world he constructed; he saw agents behind every tree and eventually died in a needless confrontation that his own paranoia played a part in provoking. There is a tragic cautionary tale there: the man who lived by the conspiracy died by it. Those who champion QAnon today might see in Cooper’s fate a mirror of where unrestrained, militant belief can lead: isolation, confrontation, destruction. Conversely, there’s also a lesson in redemption-of-sorts from Cooper’s tale. In his broadcasts shortly before his death, some recall that Cooper expressed regret over having initially believed certain fabricated documents (like the Protocols); he came to realize some parts of his theories had been hoaxes that he inadvertently spread. Though he never disavowed his major claims, that glimmer of self-correction shows that even a hardened conspiracy peddler could, when faced with evidence, adjust his stance a bit. It suggests that dialogue and revelation of facts can, at times, penetrate the armor of conspiracy belief.

In our current climate, moving away from the lure of extremist conspiracies involves a broad societal effort. This means tech platforms curbing the algorithmic amplification of falsehoods, journalists diligently fact-checking and providing context, and perhaps most importantly, communities fostering trust and addressing the real grievances that make fantastical scapegoats appealing. It’s notable that conspiracies tend to flourish in times of uncertainty and inequity—when people feel powerless, they are more inclined to believe someone behind the scenes is pulling the strings. Addressing those feelings, through better civic education, economic opportunities, and open communication between citizens and institutions, can remove the fertile soil in which poisonous theories grow.

As we step back and take in the journey from Behold a Pale Horse to QAnon, one realization stands out: these conspiracy theories thrive on our ignorance of their playbook. By learning that playbook—its recycled villains, its fear-mongering tactics, its pattern of painting the world in black-and-white—we empower ourselves to not be pawns in it. Instead, we can call it out for what it is. We can remember that real life is complex; problems have nuanced causes, not just secret villains. And we can reaffirm our commitment to seeking truth through evidence and reason, not through the seductive but ultimately destructive path of myth and paranoia.

In the end, shining light on the roots of QAnon and similar conspiracies is an act of reclaiming reality. It helps guide us away from the precipice of a society ruled by suspicion and hatred—the hallmarks of fascism and white supremacy—and toward a society where, even amid disagreements, we operate on a shared understanding of facts and a common humanity. Bill Cooper’s ghost may haunt the internet forums of today, but the more we recognize his specter and name it, the less power it holds. Understanding is the antidote to fear. By learning where our worst conspiracy fantasies come from, we take a vital step in ensuring they never determine our future.