Have you seen the videos? A young woman presses play on her smartphone, and a haunting melody of ancient flutes fills her living room. Her cat, previously lounging lazily on the windowsill, bolts upright. Ears perked, eyes wide, the feline seems transfixed by the mysterious music echoing from millennia past. This is a scene playing out in countless online videos – a meme in which people test their cats’ “ancient memories” by playing Egyptian music to see if they’ll recall the days when cats were worshipped as gods. In these funny clips, some cats gaze off as if in distant remembrance, others meow or tilt their heads curiously. Yet, woven into this playful trend is a thread of truth: in ancient Egypt, cats truly held an exalted place, straddling the realms of the everyday and the divine.

The viral videos are a lighthearted homage to a very real history. To understand why we joke about cats “remembering they were gods,” we have to imagine ourselves several thousand years in the past on the banks of the Nile. There, in the rich floodplains and bustling villages of ancient Egypt, humans and cats formed one of the most fateful partnerships in domestication. Let us leave behind the memes of the digital age and step into a sun-baked land where the boundary between people, animals, and gods was far more fluid – a land where cats indeed reigned supreme in hearts, homes, and temples.

Guardians and Companions

Long before they became divine symbols, cats likely earned the Egyptians’ admiration in a humble, practical way. Imagine an ancient grain warehouse filled with the harvest’s bounty. By day, the Egyptian sun blazes outside; by night, the cool darkness invites scuttling rodents to the feast. Enter the African wildcat, a small, agile hunter drawn to the easy prey of mice and rats. Early Egyptians noticed that wherever cats prowled, the grain stores were safe from vermin. A natural partnership emerged: the cats got a reliable source of food, and the people gained an invaluable form of pest control. Over time, wildcats essentially domesticated themselves, lingering around human settlements, warming their paws by the hearth and keeping barns free of snakes and rats. The Egyptians, in turn, welcomed and protected these four-legged allies.

By around 2000 BCE (if not earlier), cats were increasingly found in Egyptian households. They were given the affectionate name “miu” or “miut” in Egyptian (likely an onomatopoeia from the sound of a meow). With their graceful poise, keen hunting skill, and mysterious airs, cats soon moved from being just working animals to being endeared companions. Ancient tomb paintings and statues often depict family cats seated under chairs or on laps, sometimes adorned with collars or jewelry. This suggests that some cats were cherished enough to be treated almost like members of the family, especially among the wealthy. Indeed, historical accounts indicate that wealthy families pampered their cats, sometimes even dressing them in gold earrings or jeweled collars. The felines of noble houses might dine on cuts of fish and fowl fit for a human’s table. A cat’s death in the household was met with genuine sorrow – the whole family would mourn. In a remarkable mourning custom, the Egyptians would shave off their eyebrows when their cat died, signaling to all their bereavement. Only when their brows grew back did the period of grief come to an end.

The high regard for cats also manifested as strict protections. It was forbidden to harm a cat – doing so, even accidentally, was said to be punishable by death. One story from ancient historians tells of a visiting Roman who carelessly killed a cat and was lynched by an outraged mob, such was the offense. And because cats were so prized, the export of cats was strictly controlled. In fact, Egyptian authorities supposedly employed agents to retrieve cats that had been smuggled abroad, bringing them back to Egyptian soil. Imagine a kingdom dispatching envoys to foreign lands, not for gold or spies, but to bring home a kidnapped cat. This extraordinary effort underscores how seriously Egyptians valued their felines. Clearly, by the height of Egyptian civilization, the cat was not just a useful mouser – it was a creature held in the highest esteem, protected by society’s laws and loved in people’s homes.

Cats and the Gods

The companionship between Egyptians and cats was only one layer of the relationship. On a deeper level, cats became entwined with Egyptian spirituality and mythology. In a culture as old and symbol-rich as Egypt’s, animals were often seen as embodiments or messengers of the divine. The Nile crocodile, the falcon, the jackal – each had its divine associations. Cats, with their reflective eyes that gleam in the twilight and their uncanny balance of tranquility and ferocity, were no exception. The Egyptians sensed a kind of magic in cats. They saw how a cat could sit serenely for hours, then suddenly explode into action to seize a scurrying mouse. This blend of calm poise and sudden power must have seemed otherworldly – an everyday pet acting with the might of a protector.

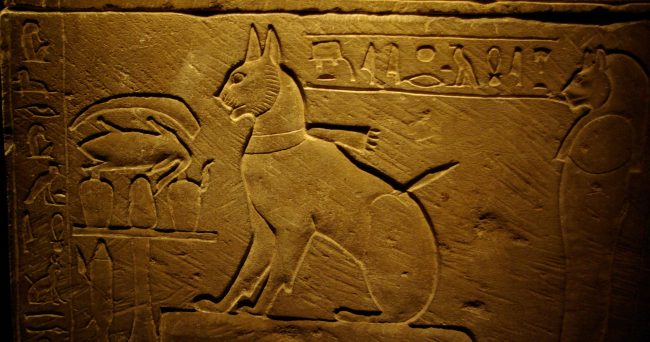

In Egyptian mythology, it was believed that gods and goddesses could take on the forms of animals to visit the earthly realm or to express certain aspects of their nature. One deity in particular became closely linked with the cat: the goddess Bastet (also known simply as Bast). Bastet was typically depicted as a woman with the head of a domesticated cat, often holding a sistrum (a musical rattle) and a basket. She was associated with the home, fertility, and childbirth, as well as with protection from evil spirits and disease. In earlier eras of Egyptian religion, a fierce lioness goddess named Sekhmet (with a lion’s head) was prominent as a deity of war and vengeance; Bastet, who may have begun as a lioness as well, gradually became seen as the more gentle, benevolent feline protector – the guardian of hearth and home. As the cult of Bastet grew, especially in the first millennium BCE, her image softened into that of the domestic cat, symbolizing grace and affection alongside power.

The city of Bubastis in the Nile Delta became the center of Bastet’s worship. There, a grand temple was built to honor the cat goddess. The Greek historian Herodotus, who traveled in Egypt in the 5th century BCE, left a lively account of the annual Festival of Bastet in Bubastis. According to his writings, each year thousands of men and women would sail down the Nile in boats, playing music and singing, to gather at Bubastis for days of joyous celebration. The festival was marked by feasting, dancing, and revelry – a carnival of devotion and merriment in Bastet’s name. Cats, as her sacred animal, roamed freely and were likely given treats and attention by the celebrants. One can imagine the city overflowing with cats during these times, each one perhaps proudly aware of its honored status amidst the human adulation.

Crucially, Egyptians did not exactly worship cats themselves as gods, but rather venerated the divine spirit they believed could inhabit a cat. To clarify: they revered cats as sacred animals of the gods, worthy of protection and care, rather than praying to individual cats. The cat was seen as a living symbol of Bastet (or other feline deities), a kind of bridge between the human world and the divine. This distinction is subtle but important. It’s not that every alley cat was thought to be a deity walking on earth, but harming that cat was an affront to the goddess who was its patron and protector. In Egyptian theology, the gods were present in many forms – in statues, in specific sacred animals, even in certain carefully chosen temple creatures (like the Apis bull). In the case of cats, there is evidence that temples kept and cared for special cats that were viewed as incarnations of Bastet. When such a sacred temple cat died, it was mummified with great ceremony and often entombed with honors.

It’s Complicated

You might assume that because Egyptians “loved” cats, those cats lived pampered lives. Many did, especially household pets. However, ancient Egypt’s relationship with cats had a more complex (and sometimes darker) side linked to their religious practices. As the spiritual significance of cats grew, so did the demand for religious offerings related to cats. By the later periods of Egyptian history (around 700-30 BCE), it became common for pilgrims visiting temples (like Bastet’s temple at Bubastis) to offer mummified cats to the goddess. These were not their personal pets, but rather cats specifically bred or obtained to be sacrificed, embalmed, and sold to worshippers as votive offerings. In a way, giving a mummified cat to the temple was analogous to lighting a candle in a church – a tangible offering to carry one’s prayers to the divine.

The result was something that jars our modern sensibilities: an industry of raising cats for sacrifice. Archaeologists have uncovered cat necropolises – vast burial grounds – containing hundreds of thousands of cat mummies. These were likely the products of breeding programs or mass roundups, where cats (including kittens) were killed humanely (often by a quick neck snap, according to some studies) and then carefully mummified by temple priests. The mummies would be purchased by devotees and placed in the catacombs as eternal gifts to Bastet. It’s a poignant thought that a culture could revere an animal so much as to make it sacred, and yet treat it as a commodity for religious ritual. However, in the context of ancient Egyptian belief, this was not seen as cruel or contradictory. The cats were sacred intermediaries; by sacrificing a cat, a person was sending a precious envoy to the gods with their prayers. It was an act of piety, and presumably the cats were afforded respect in the ritual process (their mummification was often elaborate, with some cat mummies even being placed in tiny cat-shaped coffins).

So, did the Egyptians “worship” cats? The answer is: they worshipped the divine qualities cats represented. They honored cats in life with love and protection, and in death with reverence and ritual. Cats were both beloved members of the household and holy symbols connected to the gods. This dual status is unique and speaks to the special balance cats strike – straddling the line between the domestic and the wild, the affectionate and the aloof. To an ancient Egyptian, a cat contentedly purring by the fire might be a charming pet, but if that same cat arched its back and hissed into the darkness, they might wonder if a god were moving through it, guarding the home from unseen evil.

The era of Egyptian cat worship eventually waned. By the time of the Greeks and Romans, and later the rise of new religions, the old practices faded. Temples to Bastet fell into ruin; the sacred cats of Bubastis were no more. Yet the echoes of that history have never fully died. Medieval travelers to Egypt wrote about finding cat mummies in tombs and being amazed at the idea of a civilization so devoted to cats. In modern times, the image of a sleek Egyptian cat with gold earrings, or a statue of Bastet with her regal cat’s head, continues to captivate our imagination. We see cats as mysterious, perhaps slightly aloof creatures that condescend to live with us – and the joke persists that cats remember a time when they were worshipped as gods and have never forgotten it.

The next time you catch your cat gazing intently at nothing… maybe Bastet is whispering to them through the veil of time, reminding them of its ancient stature.