A crowd gathers under the bright stripes of the circus tent, hearts pounding as a man wrapped in chains struggles inside a water tank. Minutes feel like hours… submerged… entombed in impossible knots of metal. Just when it seems no human could survive even a second longer, he bursts free, arms raised in triumph as the audience erupts in relief and astonishment. In another corner of the big top, a mighty strongman in a shimmering leotard hoists a barbell that would pin an ordinary man to the ground. Next, high above, acrobats leap and somersault through the air with effortless grace, defying gravity itself. These escape artists, strongmen, and acrobats were the superstars of their day – real people performing unbelievable feats. It was only natural that they would inspire a new kind of larger-than-life character: the modern comic book superhero.

The Superhuman on Center Stage

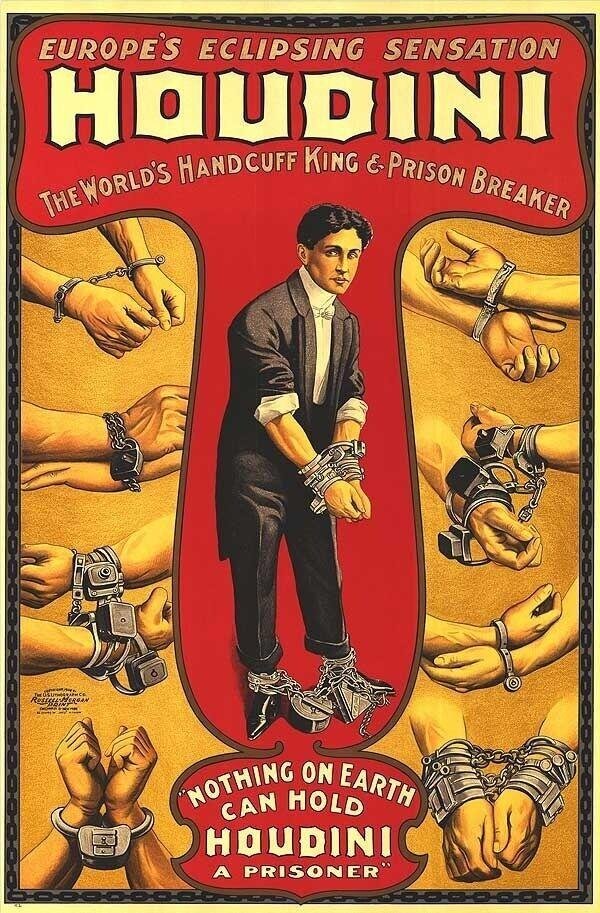

Long before superheroes flew across magazine pages in bright costumes, the public was enthralled by the daring exploits of performers who pushed the limits of human ability. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Harry Houdini became a household name by vanishing from handcuffs, escaping sealed coffins, and laughing in the face of death. He cultivated an aura of mystery and invincibility that made him seem almost superhuman. Audiences knew he was flesh and blood, yet hoped for magic – and Houdini delivered. His escapes from inescapable traps set the template for the classic superhero predicament: bound by ropes or locked in a cage, seconds ticking away, only to defy the odds and break free. Every time a caped hero slips out of an elaborate death trap at the last possible moment, the spirit of Houdini’s escapology lives on in those panels. The very concept of “escaping” danger became a cornerstone of superhero adventures, a promise that no matter how dire the situation, a true hero – like the great Houdini – will always find a way out.

Meanwhile, the circus strongman stood as a pillar of raw power that thrilled onlookers and sparked imaginations. The strongman’s act was straightforward yet mesmerizing: bending iron bars, tearing phone books, lifting horses or cars. These spectacles of strength turned performers into folk legends. Children and adults alike left the tent believing that with enough muscle and willpower, a person could become unstoppable. When Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman in the 1930s, they drew on these cultural images of strength personified. Superman’s very first appearance famously showed him hoisting a car above his head – a tableau that could have come straight from a carnival poster. In Action Comics #1, the Man of Steel breaks free from chains wrapped around his chest, just as carnival strongmen would do as a hallmark stunt. The difference was Superman needed no trickery or hidden assist to perform his miracles; he really was that strong. By exaggerating the feats of the strongman into the realm of fantasy, his creators birthed a hero who embodied the public’s dreams of ultimate strength. It is no coincidence that Superman’s costume resembled the attire of circus performers. The bright spandex costume with tight-fitting shirt and shorts, a bold emblem, and even a cape harkens back to the flamboyant outfits worn by acrobats and weight-lifters designed to show off a powerful physique. In an era before modern sportswear, circus athletes wore form-fitting garb to allow movement and flaunt their form – exactly what comic artists would adopt to display their heroes’ musculature and dynamic action. Without the influence of those showmen of the big top, our superheroes might have dressed far differently, perhaps as more ordinary soldiers or detectives. Instead, they emerged as colorful daredevils in tights and capes, dressed to captivate the eye, just like performers under the spotlight.

Daring Feats and Secret Identities

The connection between stage performers and superheroes runs deeper than costumes or stunts; it extends into the very persona of the hero. Consider the nature of an escape artist or magician: by necessity, they live a double life. On stage they are miraculous beings who can walk through walls or survive drowning, but backstage they are mortal, relying on meticulous practice and misdirection. This duality is mirrored in the classic superhero secret identity. A hero like Houdini in his street clothes was unassuming, even modest in stature – much like mild-mannered Clark Kent, the meek reporter who slips away to reveal the Superman underneath. Audiences relish the idea that someone who appears ordinary could actually possess astounding abilities hidden just out of sight. In the early days of the 20th century, Houdini’s public had a voyeuristic thrill in speculating about how he performed his escapes. Was it trick locks? Contortion? Pure magic? Likewise, comic book readers have always been fascinated by the contrast between the hero’s ordinary guise and their spectacular alter ego. The stage performer gave us a template: the notion that extraordinary powers might lie behind a curtain of ordinariness, waiting for the moment of reveal.

The influence of escape artistry on superhero mythos can also be seen in the heroes who explicitly practice those skills. It’s not just metaphorical – some comic characters are escape artists by trade. In the 1940s, readers met characters who could pick any lock and slip any knot, much to the frustration of villains. In later decades, this idea blossomed into heroes like Mister Miracle, a literal escape artist superhero who was raised in interdimensional captivity and learned to outsmart every trap. His adventures, filled with perilous contraptions and dramatic getaways, were essentially Houdini acts in spandex, proving that the art of escape itself was worthy of a superhero’s focus. And in the world of Batman – a character with no superhuman powers – mastery of escapology is part of his celebrated skill set. Writers often portray Batman freeing himself from handcuffs or straitjackets while suspended over deadly drops, a nod to the fact that he has trained to rival Houdini’s prowess. This is no coincidence: one of Batman’s early influences was The Shadow, a mysterious pulp hero created by writer Walter Gibson – who had been a professional magician and even wrote Houdini’s own magic escapades into books. The Shadow’s talent for theatrical illusion and slipping away unseen clearly informed Batman’s style. So when Batman vanishes in a puff of smoke or evades an inescapable death trap, we are witnessing a legacy that began with Houdini’s showmanship a generation before.

High-Wire Acts and Aerial Heroes

If strength and escape found their way from the circus ring into the superhero’s repertoire, so too did agility, balance, and the breathtaking elegance of acrobats. The image of a lithe aerialist flipping and twirling between trapeze bars high above a hushed crowd is pure visual poetry – and it translated effortlessly into the kinetic art form of comics. Many early superheroes were depicted as astonishing acrobats: swinging from ropes, leaping rooftop to rooftop, or delivering gravity-defying kicks. The inspiration for this can be directly traced to the popularity of acrobatic troupes and high-wire walkers that toured with the circuses. These performers showed the world that a human being, through training and courage, could move like a bird in flight or a dancer in midair. Comic artists in the 1940s, sketching a hero vaulting over a city street, had mental images of those trapeze acts to draw upon.

In fact, one of the most famous superheroes owes his very origin to the circus. Robin, the Boy Wonder, was introduced as the youthful sidekick to Batman, and his backstory is steeped in acrobatic lore. Robin was Dick Grayson, the son of a family of trapeze artists known as The Flying Graysons. Night after night, the Graysons dazzled crowds with impossible flips and catches, until a criminal’s sabotage sent Dick’s parents to their tragic deaths in midair. Bruce Wayne took in the orphaned acrobat, and with his training Dick Grayson transformed his acrobatic prowess into crime-fighting skill. Robin’s costume even resembles a circus outfit – colorful, with a flowing cape like a performer’s cape. This was a pivotal moment in comics: a literal passing of the torch from the circus ring to the superhero genre. It acknowledged that the circus was the cradle of daredevils, and who better to join the fight against evil than a daring young trapeze artist? Through Robin, readers saw explicitly how an entertainer’s gifts – agility, timing, fearlessness – could be repurposed to battle crime.

And Robin was far from the only example. Comic books introduced a slew of characters with circus or carnival pasts. Boston Brand, a trapeze artist performing as “Deadman” in a carnival, uses his acrobatic skills even after he’s murdered and returns as a ghostly superhero seeking justice. In the Marvel Universe, Hawkeye (Clint Barton) spent his youth in a traveling circus, where he learned sharpshooting and sword tricks under performers’ tutelage before becoming an Avenger. Even the mutant Nightcrawler from the X-Men, with his demonic appearance and teleportation ability, first made a living as a star attraction in a European circus freak show, where his incredible agility and acrobatic leaps were celebrated rather than feared. These stories all build on a charming premise: the circus, with its eclectic family of performers at the fringes of society, is a natural breeding ground for heroes. Under the big top, they had already been living outside the norms, honing talents that the average person could only gawk at. In comics, those talents became superpowers or the foundation for them.

The very choreography of superhero action owes a debt to those acrobats. When Spider-Man swings between New York skyscrapers on his web lines, gracefully somersaulting through gaps and perching on flagpoles, he is essentially a trapeze artist who has traded the circus tent for the concrete jungle. The creators of Spider-Man were surely influenced by imagery of high-flying circus stunts – they imbued the hero with a kind of aerial ballet quality that felt fresh and exhilarating. But in truth, it was a century-old excitement repackaged: the thrill people felt watching a person perform flips high above the ground, now given to a new generation through the comic panels of a wall-crawling, web-slinging hero.

Costumes, Color, and Theatrical Flair

Beyond feats of strength or agility, the showmanship of early performers heavily shaped the aesthetics and tone of superhero stories. In the circus, everything is larger than life. Performers wear bold costumes adorned with stars, lightning bolts, and bright patterns so even those in the cheap seats can see who’s the strongman, who’s the ringmaster, who’s the clown. This visual language carried over wholesale into comics. Superheroes emerged wearing emblems and outfits as flashy as any circus star’s attire. Strongmen influenced the design of hero costumes not only by their cuts and tights, but by the very idea that a costume should be eye-catching and symbolic. Just as a strongman might don a championship belt or a cape to suggest triumph and nobility, heroes donned capes and insignias to signal their identity and purpose. Think of Superman’s flowing red cape and bold “S” shield, or Captain Marvel (Shazam) with his golden lightning bolt and fanciful half-cape – they are essentially circus uniforms made mythic.

The notion of a mask also has theatrical roots. Many acrobats and tricksters in performance wore masks or makeup, both to create mystique and to allow a different persona to emerge under the lights. The tradition of clowns and masked magicians gave comic creators the inspiration for heroes and villains alike to hide their faces. A masked hero carried the mystique of a stage character, and this also conveniently preserved the secret identity – a practical need for storytelling that was elegantly solved by borrowing from theater and circus convention. The result was that superheroes moved through their stories as if on a fantastical stage: capes billowing as curtains, masks concealing expressions like actors, every fight and rescue a show-stopping act in the grand performance of justice.

We should also remember that before film and television, the circus and traveling shows were where ordinary people saw astonishing spectacles. Superheroes filled that cultural niche as the world modernized. By the time comic books rose to popularity in the late 1930s and 1940s, radio and cinema were also offering new forms of thrills, but the comics actively imitated the successful elements of live shows to grab attention. Early comic book covers often looked like circus posters, with sensational titles like “Amazing! Incredible!” and heroes performing some astounding feat front and center. It was pure ballyhoo, the kind you’d hear a carnival barker shout to gather a crowd. In essence, each comic was inviting readers: “Come one, come all, see the strongest man on Earth! See the daredevil who laughs at gravity! See the miraculous escape from doom!” The DNA of the circus never left the superhero genre; it simply moved from tents to pages.

Legacy of the Big Top in Comic Lore

Over the decades, comic book storytellers never forgot those early influences – in fact, they often paid homage to them directly. Villains and hero teams emerged with circus themes, acknowledging the enduring mystique of that world. A famous example in Marvel Comics is the Circus of Crime, a troupe of criminals who masquerade as circus performers. They include a hypnotist ringmaster, a strongman, a trickster clown, and acrobats – essentially a dark mirror of heroic performers. This playful inclusion shows how deeply the imagery had sunk in: even in a world of aliens and mutants, a renegade circus still captured the imagination as something both whimsical and menacing.

On the heroic side, the Justice Society and Justice League stories of the 1940s-1960s would sometimes send their heroes to investigate mysteries at carnivals or fairs, settings that allowed the characters to step into the literal space of their inspirations. Wonder Woman, in one early tale, briefly performs alongside circus strongmen and animals, demonstrating her prowess to an astonished crowd just as a performer would – blurring the line between heroine and show-woman. It’s as if the comics were tipping their hat, saying that for all the godlike powers and science-fiction elements, the heart of the superhero is still that wide-eyed amazement we felt watching an acrobat flip or a magician disappear.

Today’s superheroes, whether on screen or in print, continue to carry the torch lit by those vaudeville and circus legends. When we watch a superhero blockbuster at the theater, we’re experiencing a contemporary equivalent of the awe people once felt under the big top. The genre’s blend of awe, suspense, and triumph is a direct inheritance from the age of Houdini and his peers. Modern fans might not realize it, but the reason a dramatic escape or a show of super-strength gives us a little thrill is because, deep down, we remember that once, a real person actually did something like this. The superhero takes it a step further, into the realm of pure fantasy, but the core emotion – the gasp of “How on Earth did he do that?” – is the same.

From escape artists we inherited the idea that a hero can slip any bonds and laugh at any trap. From strongmen we got the idea of the unbeatable champion who can lift the world. From acrobats we learned that a true hero dances on the edge of danger with grace and fearlessness. These performers were the proto-superheroes of flesh and blood, and their legacy was to inspire storytellers to dream even bigger. In comic books, the feats became more impossible, the stakes cosmic, and the characters truly superhuman – but they are all standing on the shoulders of those early giants of the circus and stage.

In the end, the world of capes and panels owes a bow to the carnival stage. The next time we see a caped crusader bound in chains and submerged in a deadly tank, or catch a splash page of a muscle-bound hero holding up a collapsing building, or witness a masked vigilante swinging through the night skyline, we are seeing echoes of a past era. It’s a reminder that the fantastical heroes of today were born from the very real wonders of yesterday. The superhero, that modern myth, is in many ways a love letter to the escape artists, strongmen, and acrobats who showed the world that extraordinary things were possible. They taught us to believe in miracles performed by human hands – and primed us to imagine miracles performed by heroes beyond human limits. The circus may have packed up its tent, but its spirit lives on every time a superhero takes the stage.