In the last few months I’ve become very close to birds. I’ve been raising a family of quails in my home. My new-found connection to the emotional and intellectual lives of birds reminded me of a story I’d heard about the genius of the modern world…

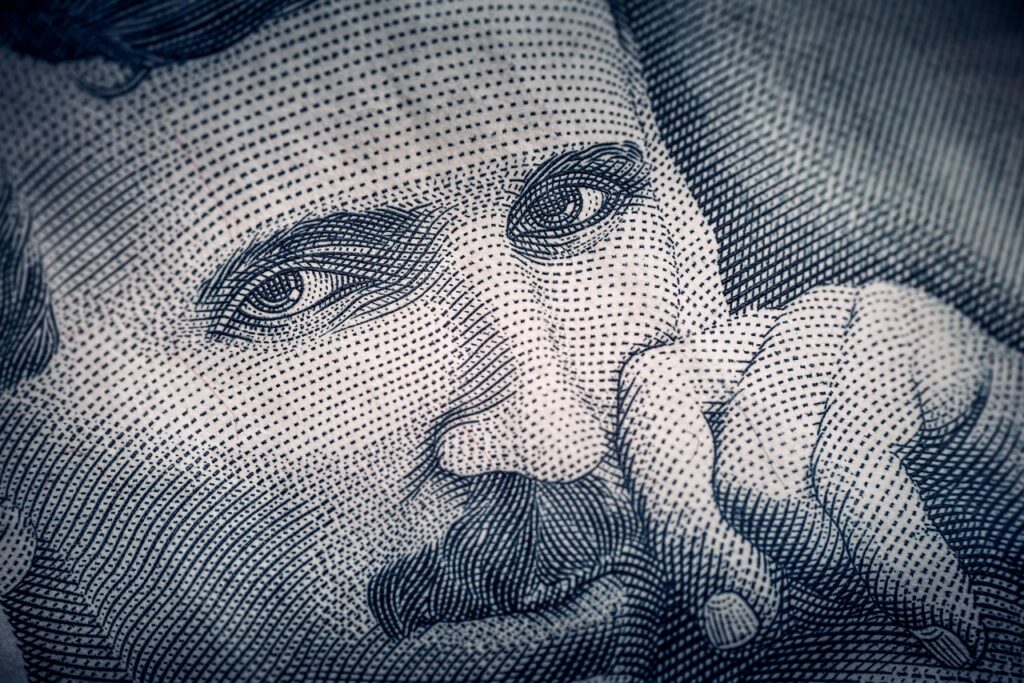

In the twilight of his life, a lone figure in a long overcoat wandered the streets of New York City, cradling a paper bag of birdseed. His once-brilliant eyes, now sunken with age, still carried a spark as he scattered grain in Bryant Park. The pigeons knew him; they fluttered down in a gray-white cloud whenever he approached, trusting that gentle man who fed them daily. Passersby might have thought him just an eccentric old gentleman who talked to birds, but this was Nikola Tesla, the genius who once electrified the world, now finding solace in the company of humble city pigeons.

Tesla’s later years were marked by solitude and financial struggle. By the 1930s, he lived in a modest hotel room in Manhattan, far from the grand laboratories of his youth. Yet every day, he ventured out to care for the pigeons. He would even bring injured birds back to his room to nurse them gently, letting them recover and share his quarters. Hotel maids complained of the mess and feathers, but Tesla persisted; the companionship of these feathered creatures had become essential to him. Among the flock there was one special pigeon, as white as fresh snow with soft grey tips on her wings. This pigeon did not fear Tesla at all – she would fly straight into his open window and perch by his desk, waiting for his affectionate nod and the handful of seeds he kept in a drawer. Over time, their peculiar friendship deepened. Tesla spoke to her as one would to a dear friend, and he felt, somehow, that she understood.

Late one night, Tesla confessed to a friend something extraordinary about this bird. “I loved that pigeon,” he said, “as a man loves a woman, and she loved me.” To many, such words were bewildering – how could a person, even a famed inventor, claim to share love with a pigeon? But Tesla meant what he said. In that pigeon’s sleek form and gentle coo, he found a genuine connection. “As long as I had her,” he explained, “there was a purpose to my life.” It was as if that bird had become a symbol of pure, uncomplicated companionship – a love neither judged nor constrained by human society. In 1922, Tesla’s beloved pigeon fell ill. The story goes that she flew into his room one last time, weak and faltering. Tesla cradled her as he had countless times before. He later described that at the moment of the pigeon’s death, he saw a blinding white light in her eyes, brighter than any of his electrical creations. In that instant, he felt his life’s work was finished. The great inventor, who had once harnessed lightning, sat alone in the silent company of his lost friend, heartbroken. He would live on quietly for years more, dying at 86 in that hotel room in 1943, but he never forgot the white pigeon that had touched his soul.

Tesla’s deep attachment to a pigeon struck many as a sign of eccentricity, even madness. People chuckled at the idea of the renowned scientist proclaiming love for a mere bird. This reaction reveals something about us: as a society, we have often viewed birds as lesser creatures, incapable of real affection or thought. We readily accept dogs as “man’s best friend” and empathize with the loyalty of a cat or the intelligence of a dolphin, but a pigeon or a sparrow? Those we dismiss with the slur “bird-brained,” implying stupidity or triviality. Yet anyone who has ever kept a pet bird would disagree: even a small parakeet or canary can show clear attachment to its human family, and larger birds like parrots have been known to pine for their owners’ presence. Birds can play, learn, and even grieve in their own ways when given the chance. Why are birds so often thought of as small-minded? Perhaps it’s the size of their brains (indeed, a bird’s brain is physically small), or perhaps it’s that they seem skittish and alien, flitting about with quick movements, or that they lack the familiar facial expressions of mammals. For centuries, even scientists underestimated avian intelligence. Early biologists noted that birds lacked a neocortex (the brain structure associated with higher cognition in mammals) and hastily concluded that our feathered friends were mostly instinct-driven. Popular culture reinforced this bias, using “bird-brained” as an insult and viewing birds as pretty creatures that sing, but not as thinkers or feelers.

More Than a “Bird Brain”: Intelligence and Affection in Birds

As I’ve come to befriend these flying family members in my care I’ve had confront some personal biases about avian intelligence. I see in my quails the qualities that Tesla saw in his pigeons. Additionally, my deep friendship with a Bornean fireback at the LA Zoo and a one-legged crow in my yard named Rogue has challenged my perceptions about what these amazing non-human beings are capable of understanding, remembering, and expressing.

Modern understanding has dramatically changed our view of bird intelligence. Far from being mindless automata, many bird species have proven astonishingly smart and even capable of emotional complexity. They simply have a different brain architecture – one that is highly efficient and evolved for the challenges of flight and survival. In fact, scientists have discovered that birds pack far more brain cells into their heads than previously thought. A raven’s brain, for example, though only the size of a walnut, contains as many neurons as a monkey’s. This dense wiring allows a “bird brain” to accomplish complex tasks akin to those of mammals with much larger brains. In other words, “bird-brained” should be a compliment, not an insult.

Let’s consider the crow, a bird often seen hopping around city parks much like Tesla’s beloved pigeons. Crows and their raven cousins belong to the corvid family, now recognized as some of the most intelligent animals on Earth. These black-feathered tricksters can solve puzzles that would stump a toddler. They use tools – a crow might bend a twig into a hook to fish out an insect from a crevice, demonstrating clever problem-solving. They have excellent memories, able to recognize individual human faces and remember who is friendly or hostile even after many years. In one remarkable account, a family who fed wild crows in their backyard found that the crows started leaving them little treasures. The birds dropped shiny trinkets on the porch: a bottle cap, a lost earring, a bit of foil, even a candy heart, as if offering tokens in return for the food they received. While scientists caution against romanticizing this as deliberate gift-giving (the crows might have simply learned that leaving objects in exchange brings more treats), the effect is a kind of reciprocity between species. The crows were clearly paying attention and engaging with their human friends in a way that goes far beyond mindless scavenging. They certainly recognize people (a well-fed crow will know the face of its benefactor and may even follow them down the street), and they appear to demonstrate gratitude or at least a sense of exchange. A truly “small-minded” creature wouldn’t be capable of such nuanced social behavior. When you lock eyes with a crow on a winter morning, it might just be evaluating you as much as you are watching it – weighing whether you are a friend, a threat, or perhaps a source of peanuts.

I also think of the flamboyantly colored toucan, with its enormous rainbow bill and curious, intelligent eyes. We often admire toucans as exotic ornaments of the rainforest, but they too have inner lives far richer than their goofy appearance suggests. People who care for toucans – in zoos or wildlife rescues – report that these birds form clear preferences and bonds. A toucan will hop eagerly toward a favored human caretaker, its body language showing excitement: rapid tail-bobbing, a gentle rattling croak, a tilt of the head as if inviting a playful interaction. Yes, toucans can enjoy being petted. Some have even been known to make a soft purring sound when their neck feathers are scratched, an astonishing display of contentment from a beaked creature. One rescued toucan named Touki became famous for snuggling against his caretaker and purring like a kitten whenever she gently stroked him. It’s a vivid reminder that birds, even those we don’t traditionally think of as pets, can experience comfort and affection. They remember those who are kind to them. A toucan may not fetch your slippers or curl up at your feet, but it might gently nibble on your fingers in a gesture of playful trust, or offer you a berry from its beak (toucans sometimes share food with their mates, and a human friend can become an honorary partner in this regard). Such behaviors dispel the notion that birds lack emotional depth; on the contrary, they show curiosity, playfulness, and the capacity to both receive and give care.

Even the pigeon – that unassuming gray bird pecking at breadcrumbs on the sidewalk – is smarter and more complex than most people assume. Pigeons can recognize individual human faces and have been shown to remember which people were friendly and which chased them away. In scientific tests, pigeons have learned to count, to differentiate between photographs, and even to understand simple rules and concepts (for example, they can be taught to distinguish between different letters of the alphabet or tell apart paintings by different artists!). They navigate home across hundreds of miles using a mysterious combination of the sun, the Earth’s magnetic field, and visual landmarks – an incredible mental feat we humans still struggle to fully comprehend. When Tesla’s cherished pigeon kept returning to him, it wasn’t just a fluke; she likely knew him apart from all others and sought him out because he was gentle and caring. Pigeons are also capable of strong pair bonds – they often mate for life, cooing softly to each other and sharing the duties of incubating eggs and raising chicks. Why then do we scoff at the idea that a pigeon could be a devoted friend to a human? Perhaps it challenges our ego to admit that these common birds we see every day have inner lives and emotions not so different from those of the pets we hold dear.

The truth is, birds are different from mammals but not lesser. Where a dog might wag its tail in joy, a cockatoo might dance with its crest held high when it sees a beloved person. Where a cat purrs to show contentment, a dove might softly coo and nibble affectionately at your ear. Birds have their own languages of love and loyalty if we listen and observe. Nikola Tesla, in his loneliness, discovered this. He poured out affection to a small white pigeon, and he felt – with an inventor’s conviction in unseen forces – that the pigeon reciprocated in her own avian way. Was he right? Science may never be able to measure a bird’s love in human terms. But consider how that pigeon kept coming back to him day after day, how she trusted him enough to spend her final moments in his presence. That sounds like love, or at least devotion, in a form we can recognize.

In a broader sense, Tesla’s friendship with a pigeon prompts us to reflect on the connections between humans and the natural world. It reminds us that empathy and companionship are not human monopolies. We share this planet with other conscious beings who experience fear, comfort, curiosity, and attachment, each in their own forms. To call someone “bird-brained” as an insult is to reveal our own ignorance of nature’s ingenuity. A bird’s mind might not write poetry or build a radio transmitter, but it can navigate a sky with no maps, craft a nest that cradles its young, and remember the face of a friend. Birds have their own wisdom – subtle and alien to us, yet very real and remarkable.

So the next time you see a humble pigeon pecking at crumbs by a park bench, or hear a crow cawing from a telephone wire, we should remember Tesla and his pigeon. We might recall that an old man found friendship and meaning in a bird’s eyes when human society had largely left him behind. And we might recognize that affection and intelligence can wear feathers as easily as fur, and that no creature blessed with the spark of life is truly small-minded. In appreciating these truths, we dispel the myth of the “bird brain” and open our hearts to a richer understanding of the living world around us. Tesla’s story reminds us to keep our hearts open: wisdom and love may dwell even in the flutter of a bird’s wings.