In the frozen steppes of Siberia, beneath layers of permafrost and ice, there once lay a colossal skull unlike any other. The wind-whipped grasslands of the Ice Age had buried this secret for millennia. When at last the skull was unearthed by modern hands, its heavy bones spoke of a creature that bridged myth and reality. This discovery gave the world the so-called Siberian unicorn—a beast both real and fantastical. It was an Ice Age giant that may have kindled human imagination long before science ever gave it a name.

Picture that ancient world: herds of woolly mammoths trudging across the plains, woolly rhinos and bison grazing on frosty grass, and early humans watching from the edges of firelight. Among these lived the Siberian unicorn, a rhinoceros so large and strange that it might well have seemed a monster of legend. The tale of this creature begins not in a fairy tale, but in the fossilized record of the earth. Its story is etched in teeth and bone, waiting to be read by those who know how to listen.

Unearthing a Legend

The first hint of this legendary beast in modern times came in the early 1800s, when a Russian princess presented a peculiar fossilized jawbone to the naturalists at Moscow University. This massive jaw, unearthed somewhere in the Siberian wilderness, puzzled all who saw it. The teeth were enormous and unlike those of any living animal. Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim, a paleontologist, examined the specimen and in 1808 announced that it belonged to a previously unknown creature, which he named Elasmotherium sibiricum. (In fact, the fossil narrowly escaped destruction in 1812, when war swept through Moscow; curators saved it from a fire that consumed many other specimens.) This dry scientific designation concealed a thrill of discovery: here was evidence of a giant, extinct rhinoceros lurking in Siberia’s past. News of the find spread, and some wondered if it was connected to the old legends of unicorns. In time, Elasmotherium gained an evocative nickname—the Siberian unicorn.

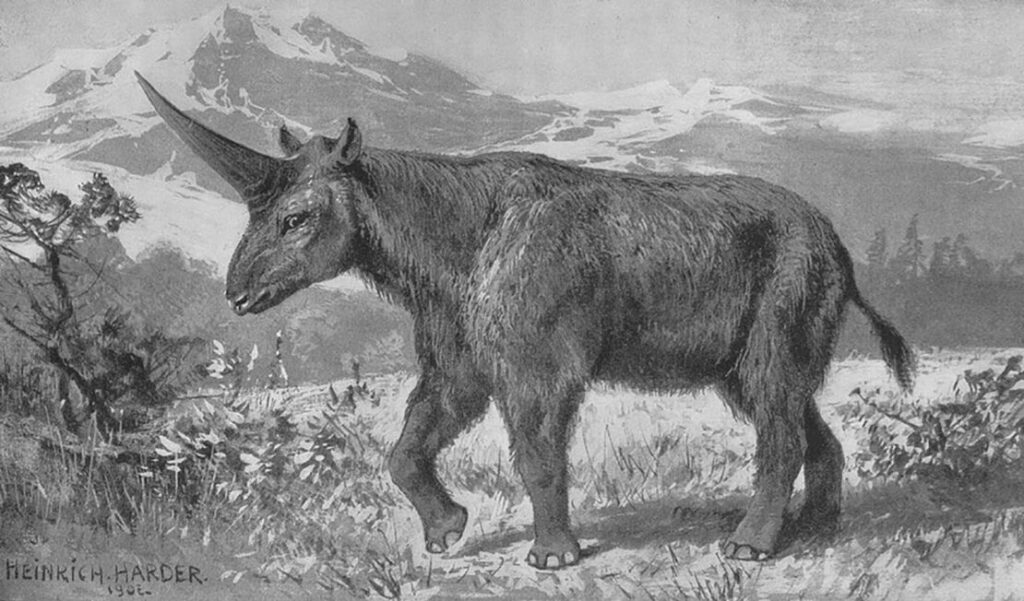

Unlike the elegant white unicorns of storybooks, this fossil creature was awe-inspiring in a different way. Imagine a rhinoceros the size of a mammoth. It stood as tall as a human at the shoulder and stretched more than four meters in length. Early reconstructions depicted it with a single colossal horn on its forehead, for the skull bore a great bony dome that seemed to be the base for such a horn. Many believed the horn could have been up to two meters long. If true, that would make it the largest horn ever carried by a rhinoceros—truly a crown fit for a legend. Holding that jawbone in Moscow, scientists realized they had in their hands the remains of a once-mighty beast that might have inspired ancient stories.

The Reality Behind the Myth

Despite the enchanting nickname, the Siberian unicorn was no delicate magical being. It was a rough-coated, muscular rhinoceros built to survive the brutal cold. Instead of a pearly white steed, picture a creature covered in shaggy fur to ward off freezing winds. This animal roamed the Earth during the late Pleistocene epoch, flourishing on the grasslands of Eurasia. Its fossils have been uncovered from Ukraine and southern Russia to Kazakhstan and beyond, painting a picture of its wide range across the steppes. And unlike a timeless myth, we can pin its existence to real dates: recent scientific studies show that Elasmotherium sibiricum survived until around 39,000 years ago, perhaps even 35,000 years ago. In other words, it walked the same ground as Neanderthals and early modern humans. That overlap raises an intriguing question: could those ancient people have passed down memories or whispers of this one-horned beast? It’s purely speculative, but one can’t help wondering if the unicorn legends that spread across Eurasia carried an echo of real encounters with Elasmotherium long ago. Even if the connection is indirect, the parallels are striking—a massive animal with a single horn wandering a stark landscape, inspiring awe.

Its famed horn was likely not a dainty spiral but a massive lance of keratin. Though no horn survives (horns decay, leaving only the bony base on the skull), the evidence of that base suggests how imposing it must have been. The horn might have been used to sweep snow from vegetation or to duel with rivals for mates. This was not the unicorn that would rest its head in a maiden’s lap; it was a titan of the Ice Age. A fully-grown Siberian unicorn weighed on the order of four tons, as much as an elephant, and carried itself on surprisingly slender legs. Few predators would have dared attack such a beast. In all likelihood, only climate and the changing landscape proved deadly. When the environment shifted—when the endless grasslands gave way to icy tundra—this specialized grazer found itself with too little to eat. Scientists believe that as temperatures plummeted and grasses grew scarce, the Siberian unicorn could not adapt in time. Its end came not with a thunderous battle or a hunter’s spear, but quietly, as the world changed around it. Like many other great Ice Age creatures (the woolly mammoth, the giant deer, and others), it slipped into extinction as the curtain fell on the Pleistocene.

Yet the idea of a one-horned creature roaming distant lands was already embedded in human folklore long before modern science described Elasmotherium. The unicorn of legend appears in the myths of many cultures—from ancient China and India to medieval Europe. Travelers’ tales of wild rhinoceroses may have fed these legends, as did the trade in mysterious “unicorn horns” (in truth, narwhal tusks from the sea). But there is another intriguing possibility: long before people understood extinction or deep time, they were finding the bones of creatures like the Siberian unicorn and weaving them into their stories.

Fossils in the Ancient Imagination

Centuries ago, ordinary people would sometimes stumble upon enormous bones protruding from the ground—a skull bigger than any known animal, teeth longer than a man’s hand, femurs heavy as stone pillars. Without a scientific framework, they made sense of these finds the only way they could: by fitting them into the stories they knew. In classical Greece, for example, huge fossils were often interpreted as the remains of giants or heroes from the age of myth. One ancient historian recounted how the Spartan people uncovered a coffin seven cubits long (over ten feet) containing gigantic bones. They declared them to be the skeleton of Orestes, a legendary hero, taking it as proof that heroes of old were indeed larger-than-life. The bones of mammoths and giant elephants, discovered on Mediterranean islands, may have given rise to the tale of the Cyclops—the one-eyed giant—because the skulls had a single large opening in the center that looked eerily like a huge eye socket. Imagine a farmer or shepherd finding such a skull; lacking knowledge of elephants, he might truly believe he had found the skull of a man-eating giant.

Further east, on the ancient trade routes of the Silk Road, travelers in the Gobi Desert might have encountered the weathered bones of dinosaurs. Legends of the griffin, a fierce creature with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle, were prevalent among Scythian nomads and later retold by Greek writers. Some researchers have noted how perfectly a fossil Protoceratops—a dinosaur with a beaked face and frilled crest—fits the image of the griffin crouched over a treasure of golden sands. To someone who had never seen a dinosaur fossil, a bleached skull with a sharp beak and a shield-like frill could easily be imagined as a mythical beast guarding gold in the desert. And in ancient China, the land of dragons, dinosaur fossils were often deemed to be dragon bones. Chinese writings from centuries ago describe people collecting “dragon bones” for medicine, not realizing they were the petrified remains of long-extinct creatures. It is likely that many dragon legends around the world were nourished by such fossil finds—tangible evidence that something big and strange had come before.

Even in medieval Europe, discoveries of unusual bones fed the folklore of the time. Gigantic ribs and skulls pulled from the earth were labeled as the remains of dragons or the giants described in biblical tales. In Austria, the curved tusk of a woolly mammoth was once displayed as a dragon’s horn, and in 17th-century France, villagers who uncovered an immense skeleton believed they had found the body of a legendary giant. Such finds would draw crowds and spark wonder, often ending up as curiosities in churches or royal cabinets, tangible proof (so it seemed) of ancient monsters.

Across the Atlantic, indigenous peoples also interpreted fossils through the lens of their cultural narratives. On the Great Plains of North America, some tribes spoke of Thunder Birds and water serpents waging epic battles; when they encountered the bones of towering mastodons or the shells of extinct giant turtles, they wove those into existing myths of sky and water spirits. In South America, stories of enormous beasts in the ground likely stemmed from finds of giant ground sloth bones or glyptodont shells. In each case, the pattern was similar: the land whispered secrets of a prehistoric world, and people responded with stories to give those secrets meaning.

These examples show a pattern repeated across cultures: whenever people dug up massive bones or unfamiliar fossils, their minds filled the gaps with wonder. In a way, our ancestors were doing their own form of paleontology with the tools of imagination and folklore. They understood that bones came from creatures of the past, but without a scientific explanation, they let myth give those creatures life again. A giant thigh bone became a hero’s relic; a mastodon skull became a cyclops; the tooth of a prehistoric shark might be called a dragon’s tongue or a giant’s dagger. Fossils were not just inert artifacts—they were clues to a hidden world, interpreted through storytelling.

From Myth to Science

The interplay between fossils and folklore reveals as much about human nature as it does about ancient beasts. Confronted with the inexplicable—be it a skeleton of a horned giant or footprints petrified in stone—our ancestors responded with stories. These myths were early attempts to understand the world, blending careful observation with boundless imagination. In a sense, those storytellers were proto-scientists: they collected evidence and tried to fit it into a narrative that made sense in their worldview. They may not have been correct in a literal sense, but they preserved something real in their tales. Dragons, giants, unicorns and thunderbirds: behind each of these fanciful beings lies a kernel of truth in the form of fossilized bone or tooth.

Today, modern science has taken up the quest to decipher those ancient clues. Paleontologists, with training and technology, are the inheritors of this age-old curiosity. With each fossil they identify, they peel back another layer of legend to reveal the creature that inspired it. But rather than stripping the world of mystery, this process often adds new wonder. It tells us that the Earth was once more fantastical than any fable—a place where real unicorns (albeit rhinoceroses) thundered across steppes and where creatures beyond our ancestors’ wildest dreams truly existed.

The Siberian unicorn is a prime example of this bridge between reality and legend. We now know it as a real animal, placed firmly in natural history, its fossils studied in laboratories and museums. Yet it’s easy to imagine how earlier peoples, stumbling upon its gargantuan skull or horn, might have whispered about unicorns roaming the far plains. Our myths, it seems, have always carried echoes of the earth’s deep past. The discovery of the Siberian unicorn’s fossils in modern times closes a circle: a legendary creature steps out of our collective imagination and stands before us in the form of an ancient rhinoceros. This revelation doesn’t diminish the unicorn’s magic—it enhances it, grounding a timeless story in the solid bones of truth. In understanding how fossils inspired folklore, we gain a new appreciation for the human capacity to wonder and for the natural world’s ability to astonish us. The unicorn may not have been the dainty horse of fairy tales, but its legacy gallops on in the interplay between the Earth’s history and human imagination.